Women Pioneers of Italian Graphic Design

Introduction

The history of the arts and professions has predominantly been written from a male perspective. For at least 20 years, AIAP has been promoting and curating various projects investigating women’s design issues from different standpoints, such as the AWDA (AIAP Women in Design Award). In terms of historical research, since 2019, the AIAP CDPG has curated a series of exhibitions united by the provocative term ‘PINK‘.

Initially, the project showcased the work of female graphic designers who were active in Italy between the 1940s and 1970s, a period of significant societal change in Italy, marked by an economic boom and the emergence of new customs. This was a period when the employment of Italian women, even in professional sectors that were in some ways ‘privileged’, was influenced by stereotypes and preconceptions about women’s roles. Over time, PINK has evolved into a more comprehensive project, showcasing female designers and graphic designers from various time periods up to the present day.

This thematic path introduces us to the lesser-known stories of women in graphic design, who were mostly excluded from the major histories of Italian and international design. These include Brunetta Moretti Mateldi, Anita Klinz, Claudia Morgagni, Simonetta Ferrante, Jeanne Michot Grignani, Umberta Barni, Carla Gorgerino, Ornella Linke Bossi, Alda Sassi (Alsa) and Lora Lamm.

By displaying posters, books, sketches, drawings and photographs, we can not only view extraordinary graphic artefacts, but also gain insight into the lives of autonomous, courageous and talented women who balanced their professional and personal lives. They are role models that have rarely been outlined or discussed until now.

The Role of AIAP

Following the split from the Advertising Technicians component in 1955, the Italian Association of Advertising Artists (AIAP) was formed. Four female designers appeared among the 70 ‘split’ members led by Franco Mosca: Umberta Barni and Brunetta Moretti Mateldi of Milan, Alda Sassi of Turin and Annaviva Traverso of Savona.

The 1963 AIAP yearbook (with a beautiful cover by Franco Grignani) lists 199 members, 13 of whom are women. Of these, only seven sent examples of their work for publication: Umberta Barni, Brunetta Moretti Mateldi, Claudia Morgagni, Elena Pinna, Annamaria Sanguinetti, Rosaria Siletti Tonti (who was originally from Naples but was active in Milan at the time) and Verbena Valzelli Guerini (who was from Brescia).

Brunetta Moretti Mateldi played an active role in the Association in its early years. As well as being among the 70 ‘splitters’, she received the Garter Prize in 1956 (a semi-serious award intended to consolidate relations between the Association and the world of communication).

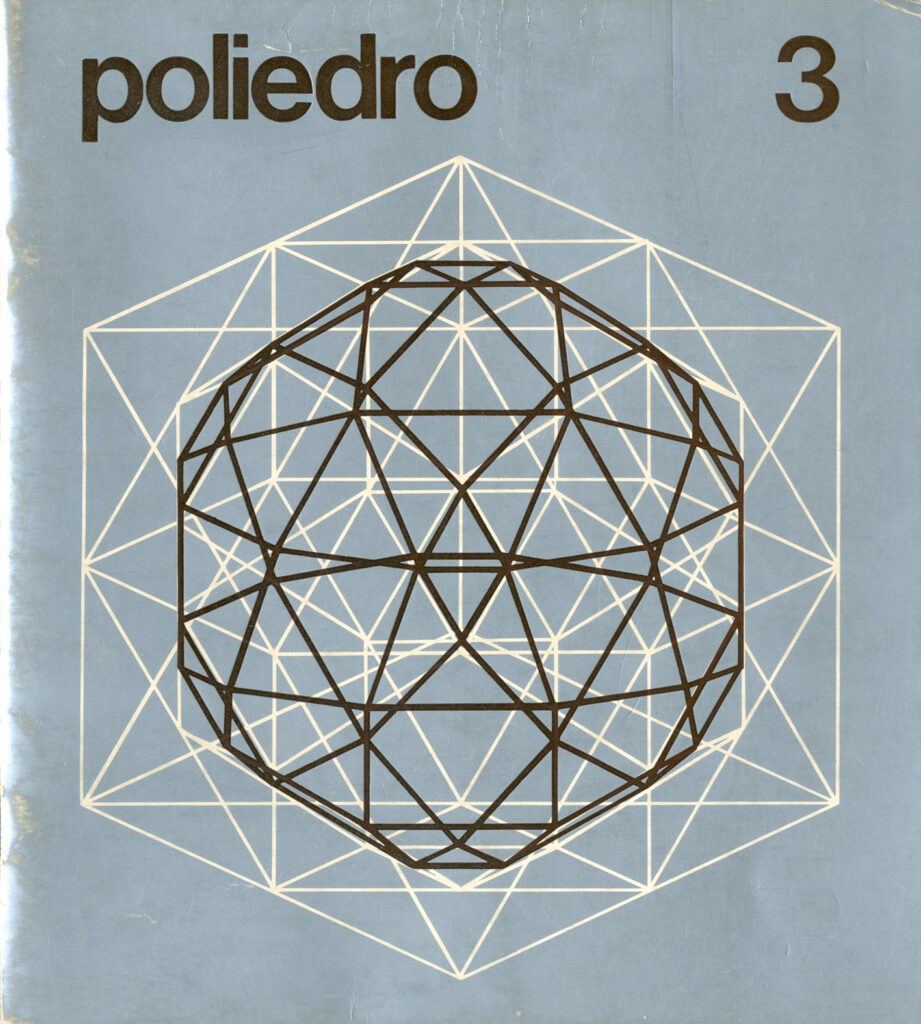

Ornella Linke Bossi, appointed an honorary member in 2024, has been an AIAP member since 1964. She was particularly active in the life of AIAP in the following years, designing some covers and editing texts for the Poliedro bulletin. In 1970, she was appointed vice-president for a three-year term.

Simonetta Ferrante has also been a member of the Association since 1978 and was appointed an honorary member in 1985. She was one of the first professionals to open an independent studio in the early 1960s.

Why Pioneers?

One of the reasons why some pioneers can be identified is due to professional autonomy and management roles. We are talking about those female professionals who, in the years following the Second World War, started their own businesses or who had management tasks (such as Anita Klinz), taking on responsibilities, covering different roles, interacting with clients and suppliers.

Although many of them worked and lived in a city like Milan, which was undergoing rapid social and industrial evolution, in constant contact with the world, of which it was one of the centres in those years, they embarked on autonomous and important careers, in a predominantly male professional context. A context, from a social point of view, that conditioned them or tried to steer them towards stereotyped roles.

Precisely, the multiplicity of roles is another factor. For a woman at the time, carving out her own autonomous profession was, to all intents and purposes, an almost heroic achievement, if the profession had to go hand in hand with conventional social and cultural roles: being a wife, being a mother, looking after the family home, looking after the offspring.

The graphic designer’s profession already allowed for flexible management of one’s time, but independence could be relative if one was unable to achieve even substantial financial results. This multiplicity of roles evidently weighed differently for women if not more than for men. And as such, it should be considered as a further element of evaluation and enhancement.

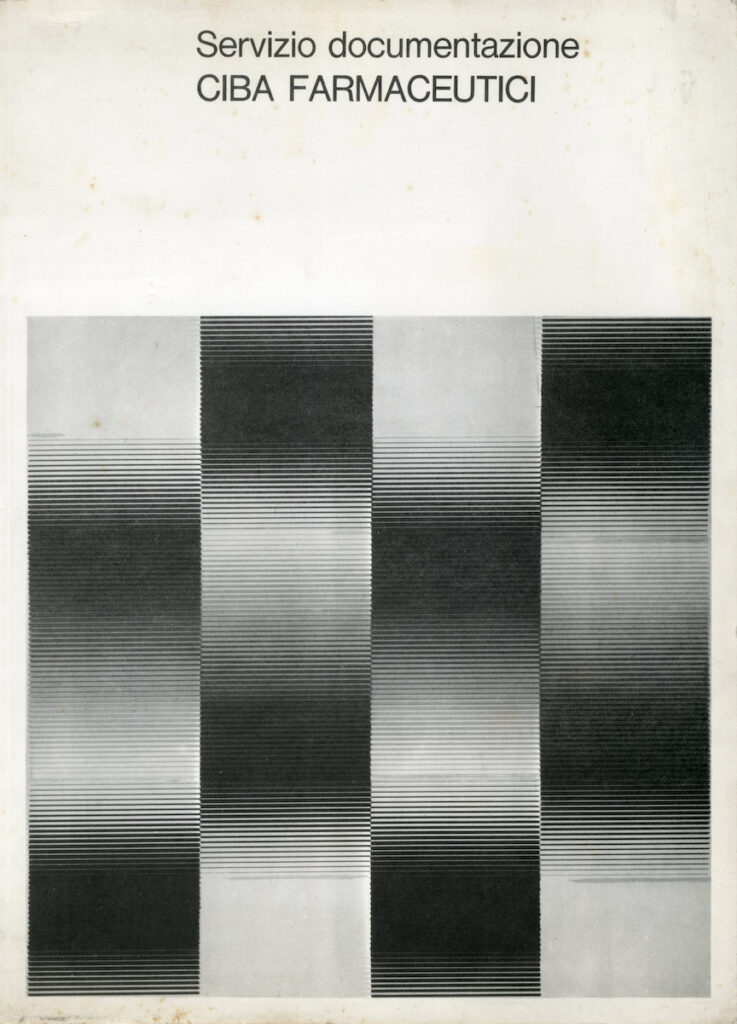

Another argument that is considered valid is that of the variety of orders and the inconsistency of the theme, widely adopted in the past, of a specific professional reserve. Female graphic designers, just like their male colleagues, contrary to what the prejudices of the time and some sources indicate, dedicated themselves (and dedicate themselves today) to a variety of fields that go far beyond drawing for a fashion house, department store or in any case for products aimed at the female public. They interact with sectors such as heavy industry, chemistry and pharmaceuticals. Producing not only billboards or posters, but campaigns, visual identities, product packaging, and books. Thus contributing to the development of the industrial culture that characterised the Italian economic boom and the country’s rebirth.

This variety is also expressed in terms of visual languages, not only related to illustration and expressive sign (a mode also conditioned by the training they had access to both before and immediately after the war), but also to some of the most up-to-date trends of the time.

Umberta Barni

She is one of the 70 AIAP founder members and exhibited in both editions of the Mostra Nazionale degli Artisti Pubblicitari (National Exhibition of Advertising Artists), held in 1956 at the Palazzo della Permanente and in 1959 at the Villa Palestro Modern Art Gallery in Milan and organised by the Association.

Simonetta Ferrante

In the mid-1970s, she left the graphic design studio and founded the Centro dell’Immagine e dell’Espressione (Centre of Image and Expression), devoting herself to teaching and painting. Later, the collaboration with the Italian Calligraphic Association marked a new phase in her artistic production that she still carries on today. She is an honorary member of AIAP.

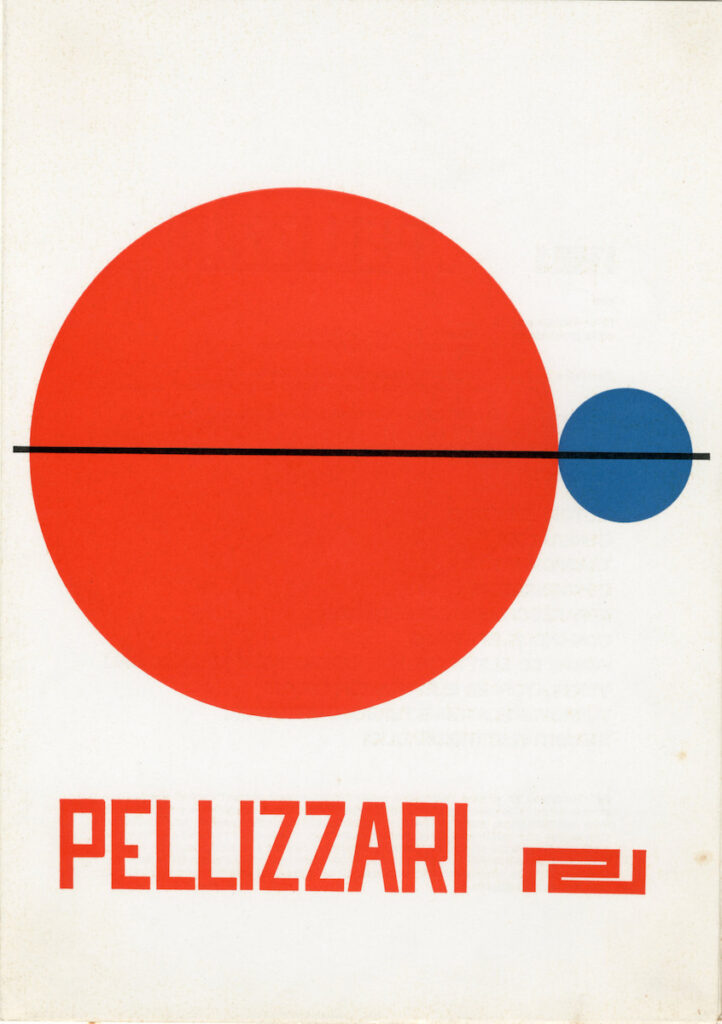

Carla Gorgerino

Jeanne Michot Grignani

In the 1950s, she worked for well-known Italian companies, such as Borsalino, Necchi, Singer and Pirelli, creating original advertising artifacts. Between 1950 and 1955, she designed a line of raincoats for Pirelli. Her style represents the Italian economic boom.

Anita Klinz

She joined Mondadori in 1951, already back then Italy’s largest publishing house, and was rapidly appointed head of the graphic design department. She handled books of all kinds, from encyclopaedias to poetry books, but also periodicals and series sold at newsstands, such as “Gialli” and “Urania”, novels that introduced science fiction to Italians. In fact, she invented the recognisable round frame to accommodate Karel Thole’s illustrations. For other series, she also collaborated with other well-known illustrators, including Ferruccio Bocca and Ferenc Pintér.

Her skills were so appreciated that Alberto Mondadori called her in 1958 to participate in the adventure of Il Saggiatore, where she continued to invent iconic covers, such as for the series “I Maestri dell’Architettura Contemporanea”.

In the 1970s, she worked particularly on magazines, including «Duepiù» and «Grazia» as well as newspapers such as «Il Giornale di Bergamo» and «Il Mattino di Padova».

In 2012, she was awarded the AWDA Lifetime Achievement Award.

Ornella Linke Bossi

In 1979, she founded her own graphic design studio together with Elena Consonni and Luisa Montobbio, specialising above all in audiovisual and social and cultural communication.

She has also been a lecturer at the IED in Milan.

In the 1960s, she was particularly active and present in the life of AIAP (of which she has been a member since 1964), curating a number of covers and editing texts for the bulletin entitled «Poliedro». Over the 1970-1973 period, she was vice-president of the Association. In 2015, she was awarded the AWDA Lifetime Achievement Award.

Brunetta Moretti Mateldi

She was among the 70 members who, in 1955, approved the split from the Advertising Technicians section, giving life to AIAP. In the following years, she actively participated in the active life of the association.

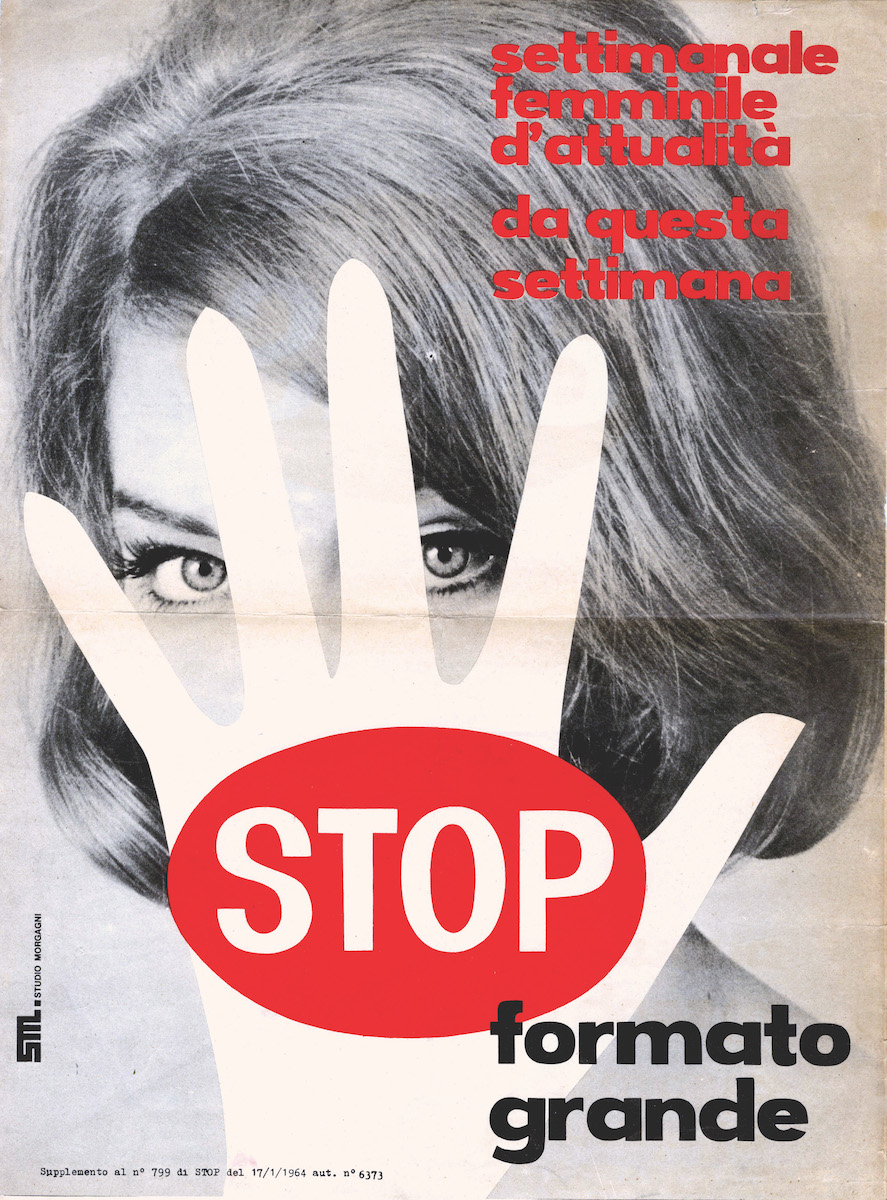

Claudia Morgagni

In 2019, she was awarded the AWDA Memorial Award as a role model for women designers and women.

Alda Sassi

Her activity designing posters for shipping companies (Lauro, Italia, Lloyd Triestino) is worthy of note.

Useful References

Breuer, G., & Meer, J. (2012). Women in Graphic Design. Jovis Verlag.

Biribanti, P. (2018). L’ironia è di moda. Brunetta Mateldi Moretti, artista eclettica dell’eleganza. Carocci Editore.

Bucchetti, V. (2016). Le donne di Lora Lamm. In R. Riccini (Ed.), Angelica e Bradamante. Le donne del design (pp. 207–224). Il Poligrafo.

Cerritelli, C., & Ossanna Cavadini, N. (Eds.). (2016). Simonetta Ferrante. La memoria del visibile: segno, colore, ritmo e calligrafie. Silvana Editoriale.

Dradi, M. (2017). Brunetta, Giulia, Umberta. Primi profili. In R. Riccini (Ed.), Angelica e Bradamante. Le donne del design (pp. 185–191). Il Poligrafo.

Ferrara, M. (2012). Design and Gender Studies. PAD. Pages on Arts and Design, 7(8). http://www.padjournal.net/design-and-gender-studies/?lang=it

Guida, F.E., & Grazzani, L. (Eds.). (2011). The Unbroken Sign. Simonetta Ferrante. Graphics between Art, Calligraphy and Design. AIAP Edizioni.

Guida, F.E. (2016). Claudia Morgagni, Commitment as a Professional Model. In 09 F CM – Fondo / Folder Claudia Morgagni (pp. 1–16). AIAP Edizioni.

Guida, F.E. (2020). Beyond Professional Stereotypes. Women Pioneers in the Golden Age of Italian Graphic Design. PAD. Pages on Arts & Design, 13(19), 14–39. https://www.padjournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/PAD19-014.pdf

Gunetti, L. (2018). Ornella Linke-Bossi: The Project and the Research. In C. Ferrara, L. Moretti, & D. Piscitelli (Eds.). AIAP Women in Design Award, vol. 2 (pp. 26–29). AIAP Edizioni.

Pansera, A. (2017). Anita Klinz. In R. Riccini (Ed.), Angelica e Bradamante. Le donne del design (pp. 77–90). Il Poligrafo.

Pitoni, L. (2022). Ostinata bellezza. Anita Klinz, la prima art director italiana. Fondazione Arnoldo e Alberto Mondadori.

Vinti, C. (2024). La grafica italiana del ‘900. Giunti.